I demystify some of art world jargon surrounding applying to art calls. Things you need to learn when you are getting into the art scene.

Applying to Art Calls

My mom asked me recently why I wouldn’t just get into any shows I applied for. That’s when it occurred to me that many folks might not know what some of the terms mean. Things like “open call” or “juried show.” So I thought I’d take this post to talk about what applying to art calls looks like for me. I started writing in my February work post and when I got to six paragraphs, I realized it needed to be it’s own post!

What is an open call

An “open call” means that a museum or gallery or group is looking for artists’ submissions. A group can be a civic org or local government looking for artists for murals in schools or public spaces. There are usually a lot of parameters on any given call. Your age, your geographical location, when the work was completed, medium, subject matter, and size are just a few variables that a call can specify. Before I apply to a call, I read these criteria carefully and if I don’t match up to any of them, I move on. There is NO REASON to apply to a call if you don’t meet basic criteria. You can and will get kicked out before the committee even sees your work. You’ve wasted your time and maybe your money applying to something where you don’t fit.

If I meet all the basic biographical and geographical criteria, then I move on to the work-specific parts. I check to see if I have work in the theme they are looking for? And does it meet the materials and size requirements? Or is there enough time before the call closes to make work specifically to fit the criteria? There are so many points along this path where I can miss the submission requirements. And that’s okay, there’s a lot of calls out there. I can move on to the next one and maybe meet them or finish something new in time. (This year, I’m using the large number of ALWCA open calls as prompts to make work and push myself.)

My Into the Unknown video

I would love to submit my recent video to an open call! But open calls for videos are fewer and farther between. I haven’t spent any time looking for calls to fit this video. It’s on my to do list for this quarter. (I talk about where to look for open calls below.)

Costs

There’s usually a cost associated with a call. Between $10-$50 to enter one to three pieces of work is typical in any given call. This money ISN’T payment to get into the show! Rather it is money to pay the jury for their time and expertise to curate the submissions. It’s simultaneously too much for artists, because it limits how many calls you can enter, and not enough for the people doing the hard work of curating the shows.

How much an entry fee costs is part of my calculations for applying. If it’s a show I feel like I have a solid chance at, I will pay it. If it feels like more of a stretch goal, I’ll opt out if the fees are higher. For the three shows I’ve entered this past month, I’ve spent $45 total. It’s part of doing business as an artist. I report those fees on my taxes as part of my art business.

Where to find calls

There are multiple online clearing houses where you can access open calls. Call for Entry, or CaFÉ, is the one I’ve used most often. There’s also Entry Thingy and a few others. These sites are usually free to join. You can sort calls by many different criteria so you can drill down and find calls that meet your needs. Individual organizations can also put out their own calls. I’ve been eyeballing this call from the National Gallery of Art. The social media piece (that’s the YouTube video below) is hilarious and am thinking of applying to it. I have an idea, I just need to write up the proposal.

One of the big reasons I joined Women’s Caucus for Art was because their mission is to give women (and women presenting and nonbinary people) exhibition opportunities. My local chapter is full of amazing folks! I’ve loved getting to know them and exhibiting alongside them over the past five years. There are chapters across the country. If that sounds like something you’d like to learn more about, here’s the chapter list from the national site. If there’s no chapter near you, you can become a member-at-large.

What is a juried show?

A “juried show” means that there is a committee of people who are tasked with looking at all the submissions from the call and putting together a body of work around the specified theme. The jury is usually made up of one to five people. They can be artists themselves, or work for the gallery or museum, or they are involved in the community in some other way.

In my experience the few times I’ve met jury members, they are people who are art lovers and are interested in making something interesting, thought-provoking, and cohesive for people to look at and enjoy. My younger, harsher self viewed this group as gatekeepers looking to turn people away for the joy of being haters. And maybe there are a few of those out there but most juries are looking for the work that best exhibits the theme of the call and fits in the body of work coherently.

Now that I know a little bit more about how this works, I am fascinated when I go to group shows and see what the jury has chosen and how they’ve decided to organize it for viewing. Puzzling out those choices are sometimes as interesting to me as the art. It is a form of art in and of itself.

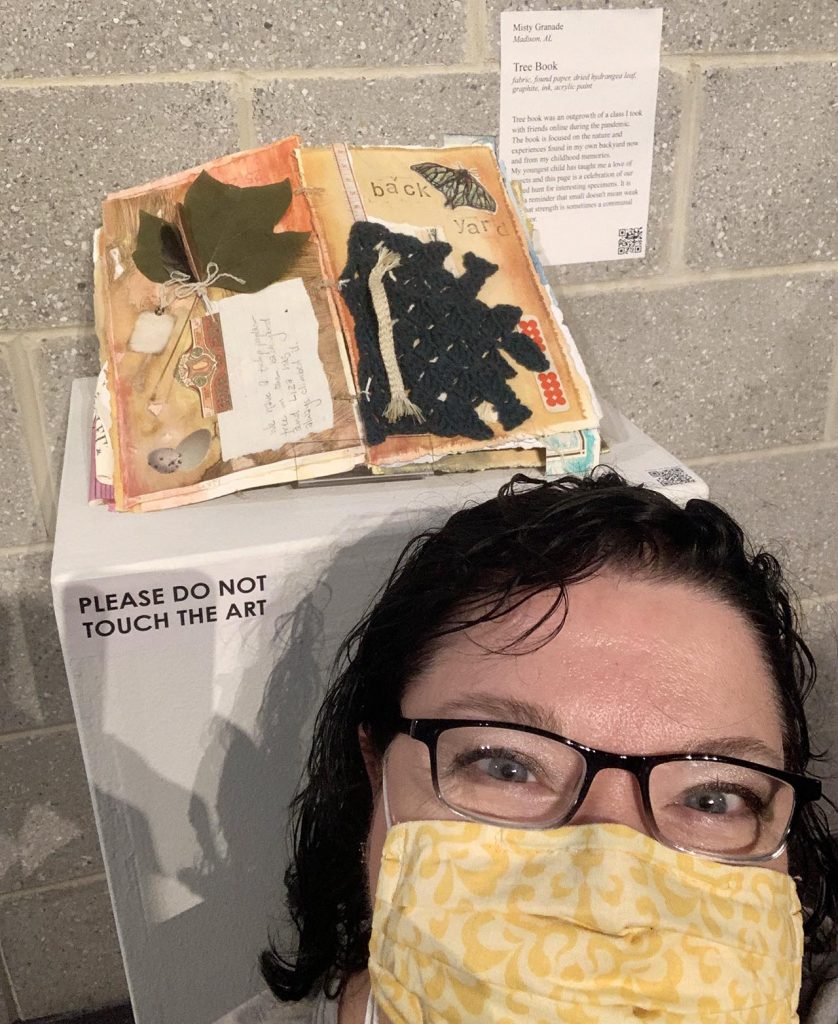

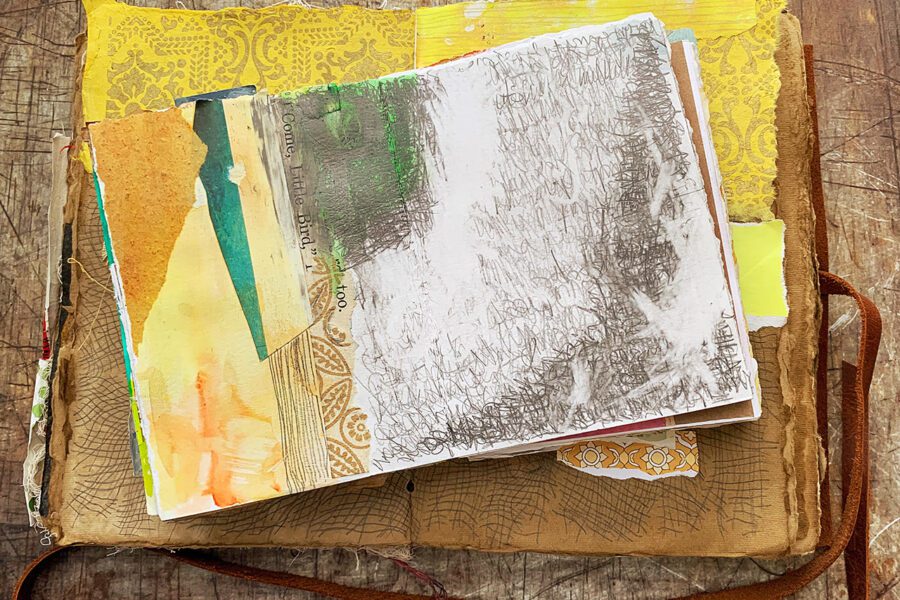

Being solicited for a juried show

Years ago, I was solicited on Instagram to enter a show call from the AnnMarie Sculpture Garden & Arts Center. I was showing off my Tree Book on Insta and someone from their staff pointed me to the call and encouraged me to apply. At first, I was skeptical that it was legit (as we should all be when cold solicited on social media). But indeed it was legit and it led me to enter and be accepted to this magical show!

What about a show where it’s just one person’s work?

This is called a solo show. Galleries will open up for proposal submissions a few times a year or will query specific artists for proposals. Galleries often keep a planned rotation going where they could be booking artists out a year or two or more. When I first started, I was shocked to learn that booking eighteen months out is pretty normal. It’s a cycle that you have to stay on top because once you fall out of it, it takes a while to get back into the groove. It takes a lot of planning and frankly more spreadsheets that I ever dreamed of when I was dreaming of being an artist as a girl.

I’ve had two solo shows in the past ten years at my local venue, Lowe Mill, and another time for ALWCA in their gallery inside Lowe Mill. I’ve also had a solo show at an upscale frame shop that works with local artists. That’s four in ten years which doesn’t sound great. When you realize each of those four shows represents work over the course of about a year to fourteen months each, then saying that’s four and a half years of work, sounds MUCH different.

My first solo show

It is a heavy lift to have enough work for a whole show. As I just said above it takes months, if not years, to prepare. I both love it and hate it. When I first applied to Lowe Mill I KNEW I would get rejected. I was shocked when I got the acceptance. Some part of me will always be a little bit surprised by that turn of events. I worked my butt off for that first show. And I stayed strung out on anxiety and nerves about doing all of it wrong. I was the very definition of “doing it scared.”

But it was a success! So many family and friends turned out for that opening and when I think about my anxiety and nerves, I also remind myself to think of everyone who supported me that first show. I sold seventeen of twenty one pieces and the gallery manager told me it was one of best shows they’d had in terms of number of pieces sold.

If you want to read more about my first show, Conversational Sexism, and see the pieces, you can do that here. Each of the pieces have links to blog posts where you can read about different parts of that process.

What is a show proposal?

Some calls will ask for proposals. Every solo show I’ve applied for, I’ve had to submit a proposal. This may ask about work you have already made or work you are anticipating making for the show. This is often site specific where you talk about how the work you want to show will fit into their specific venue. The venue will often supply their space dimensions, sometimes with diagrams. Which means there’s usually a lot of measurements to calculate by adding up the size of your pieces and seeing if they will fit in the gallery space. You will likely have to submit some combination of your artist statement, artist bio, CV/resume and contact information including your social media links and website. You also typically have to submit work samples.

This was a super intimidating process to me when I first did it. It can be awkward writing about your work if it isn’t something you’ve done much of before. Artist bios are often written in the third person so that makes it even weirder. Doing it the first time is the by far the worst. Once you’ve done it, save every piece of writing you do so that if you do it again you have a template.

There is a big move now for artists to write about their work more naturally, leaving lofty art speak by the wayside. It’s a move I wholeheartedly approve of since that kind of overly academic writing can create barriers to entry for many people who might otherwise enjoy art.

Many gallery managers are happy to answer questions about this process. My first show, the gallery manager was amazing and held my hand through the whole process. And once again, if you are a part of a professional artist organization, they will often have materials like prerecorded classes or workshops you can access or fellow members might help answer your questions.

Costs associated with gallery shows

It is normal for galleries to ask for 30-50% of the price of a piece of art sold. So for my Conversational Sexism show, eighteen of the twenty one pieces were $100. Lowe Mill took 40% of each sale. I got $60 for each of those sales. The percentage that galleries charge covers things like paying staff, heating and cooling for the space, and marketing and hundreds of other things that I don’t want to worry about. This is the cost of doing business as an artist. And while I remember very vividly feeling like 40% was VERY high, I’ve come around to really appreciating the work galleries do that I don’t have to. From Lowe Mill’s website:

Lowe Mill ARTS & Entertainment is the largest privately-owned arts facility in the United States. With a focus on visual arts, this historic textile mill has been redeveloped into 153 working studios for over 300 artists and makers, 7 galleries, a theatre, community garden, and performance venues.

That isn’t something I can create by myself. It’s a huge draw for our community and surrounding area. So I don’t begrudge that 40% anymore because they are doing work and reaching people that I just absolutely cannot on my own.

Contracts

Any show will have a contract. They usually have stipulations for exhibition dates, reception dates, install and removal dates, what the compensation split will be, what the artist is required to provide (usually an inventory and price list so price cards can be made), how the work is supposed to be prepared for hanging (many galleries have hanging systems that need work to have wire fixed on the back of pieces for hanging), and a liability waver. If the venue isn’t offering a contract or your contact person is being weird when you ask about a contract, that’s a red flag.

In my experience, coffee shops and wine bars are sorta notorious for playing loosy goosey with contracts. Not necessarily because they are trying to take advantage of artists but because they aren’t well versed in how these things work. Use your discretion when dealing with them.

If a venue requires you to pay upfront to show your work, that’s a red flag. I was once solicited for a show where showing my work was free but I’d be required to buy a book of tickets to sell in order to be featured. That’s a scam. It takes advantage of artists who are desperate to get their work out there. Don’t fall for it.

Being a part of a professional artist organization can also help you vet venues and opportunities. It wasn’t a benefit I anticipated when I joined ALWCA. Thankfully though, there are many artists in the group that have been working in this area for years. They know who is trustworthy and who is new and untested in the community. We also tend to let each other know when there’s something wacky going on in the area.

Why do I do this?

This is not an unreasonable question. I ask it on the regular, quietly to myself and sometimes out loud to my partner. Because the process I just described above? It takes a tremendous amount of time and brain cycles. It calls for organization and planning, some days more than I have honestly. Also it can and does regularly distract me from the art making itself. That’s a problem I have to manage too.

Here’s the super personal truth though…

I know that my work isn’t pretty in a way a lot of people like for their personal space. Sure, some things that I make are lovely if you like that sort of thing and vibe with it. But what I make isn’t going to get chosen by Home Goods or Kirkland’s to be a part of their spring collection. There’s not a lot of mass appeal.

My work is weird and often deconstructed to the point of oblivion. There’s usually a lot of concepts embedded in it that make for bad sofa art. The home for that sort of work is usually galleries and museums. It just is. And I understand that there’s some classism/elitism/and probably some more -isms baked into that. That’s why to go along with making that work, I spend so much time trying to make it accessible here.

There’s also the personal validation for me of having work in galleries and museums. My personal definition of being a “real” artist is having my work in galleries and museums. Understand, I don’t hold anyone else to that standard and most of the time, I don’t even hold myself to it. But it’s there for me. I used to try to talk myself out of it or explain it away. But it’s part of my artist DNA. And I think I’m finally done trying to pretend that it’s not.

Do you have questions about this process? I’d love to hear them! Email me or start a conversation by leaving a comment on this post! If you’d like to keep up with what I’m working on, I’d love to have you as a newsletter subscriber. I include blog posts from here, cool things I find online, and pictures of my dogs. Sign up here.

Thanks so much for this lesson and some great resources too. I found your name on my local art caucus (I’m in Alabama too – just WAY down at the bottom of the state.) I’m going to try to save this post to reference again. I appreciate it more than you know.

Hi Hope! So glad to meet you virtually! And I’m pleased this was helpful information for you. I hope I see you at the next caucus meeting!!